what was the march on washington movement designed to do?

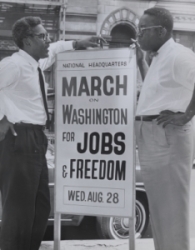

Photo by Marion S. Trikosko, LOC, LC-U9- 10344-14

The event focused on employment discrimination, civil rights abuses against African Americans, Latinos, and other disenfranchised groups, and support for the Civil Rights Human activity that the Kennedy Administration was attempting to pass through Congress. This momentous display of borough activism took place on theNational Mall, "America's Front Chiliad" and was the culmination of an idea born more than than xx years before.

While the March was a collaborative effort, sponsored past leaders of diverse student, civil rights, and labor organizations, the original idea came from A. Philip Randolph, a labor organizer and founder of the Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters and the Negro American Labor Council (NALC). His vision for a march on the Nation's Capital dated to the 1940s when he twice proposed big-calibration marches to protest segregation and discrimination in the U.South. armed services and the U.Due south. defense force industry and to pressure the White House to take action. The pressure worked. President Roosevelt signed Executive Club 8802 (Prohibition of Bigotry in the Defense Manufacture, 1941) and President Truman signed Executive Order 9981 (Desegregation of the Military machine, 1948), and Randolph cancelled the marches.

Photograph past Orlando Fernandez, LOC, LC-USZ62-133369

Past the 1960s, a public expression of dissatisfaction with the condition quo was considered necessary and a march was planned for 1963, with Randolph every bit the titular head. Joining Randolph in sponsoring the March were the leaders of the five major ceremonious rights groups: Roy Wilkins of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP),Whitney Young of the National Urban League (NUL),Martin Luther King, Jr. of theSouthern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC), James Farmer of Congress On Racial Equality, andJohn Lewis of the Student Irenic Coordinating Committee (SNCC). These "Big Half dozen," every bit they were chosen, expanded to includeWalter Reuther of the United Automobile Workers (UAW),Joachim Prinz of the American Jewish Congress (AJC), Eugene Carson Blake of the Commission on Religion and Race of the National Council of Churches, and Matthew Ahmann of the National Catholic Conference for Interracial Justice. In addition,Dorothy Height of the National Council of Negro Women participated in the planning, only she operated in the background of this male person dominated, leadership group.

The March was organized in less than 3 months. Randolph handed the day-to-mean solar day planning to his partner in the March on Washington Movement,Bayard Rustin, a pioneer of the 1947 Journey of Reconciliation and a brilliant strategist of nonviolent direct action protests. Rustin planned everything, from training "marshals" for crowd command using nonviolent techniques to the sound system and setup of porta-potties. In that location was also anOrganizing Manual that laid out a statement of purpose, specific talking points, and logistics. Rustin saw that to maintain order over such a large oversupply, there needed to be a highly organized back up structure.

Rustin coordinated a staff of over 200 civil rights activists and organizers to assist in publicizing the march and recruiting marchers, organizing churches to heighten coin, coordinating buses and trains, and administering all of the other logistical details. In many ways, the March defied expectations. The number of people that attended exceeded the initial estimates made by the organizers. Rustin had indicated that they expected over 100,000 people to attend - the final approximate was 250,000, 190,000 blacks and sixty,000 whites.

Photo by Warren K. Leffler, LOC, LC-U9- 10360-five

With that many people converging on the city, there were concerns about violence. The Washington, D.C. police force mobilized 5,900 officers for the march and the regime mustered 6,000 soldiers and National Guardsmen as additional protection.President Kennedy thought that if there were any issues, the negative perceptions could undo the ceremonious rights bill making its manner through Congress. In the end, the crowds were at-home and in that location were no incidents reported past law.

While the March was a peaceful occasion, thewords spoken that day at theLincoln Memorial were not just uplifting and inspirational such equally Martin Luther King Jr.'s"I Have a Dream"speech, they were also penetrating and pointed. There was a list of"Ten Demands" from the sponsors, insisting on a fair living wage, off-white employment policies, and desegregation of schoolhouse districts. John Lewis inhis oral communication said that "nosotros exercise non want our freedom gradually simply we want to be free now" and that Congress needed to pass "meaningful legislation" or people would march through the South. Although the SNCC chairman had toned downwardly his remarks at the request of white liberals and moderate black allies, he withal managed to criticize both political parties for moving too slowly on civil rights. Others such every bitWhitney Young andJoachim Prinz spoke of the need for justice, for equal opportunity, for total access to the American Dream promised with the Declaration of Independence and reaffirmed with the passage of the 13th, 14th, and 15th Amendments. They spoke of jobs, and of a life costless from the indifference of lawmakers to people'south plights.

In the end, after all of the musical performances, speeches, and politics, it was the people that truly made the March on Washington a success. They brought box lunches, having spent all they could spare to go to Washington; some dressed every bit if attention a church service while others wore overalls and boots; veterans of the Civil Rights Movement and individuals new to the problems locked artillery, clapped and sang and walked. Many began without their leaders, who were making their manner to them from meetings on Capitol Hill. They could no longer be patient and they could no longer be held back, and and then they started to march - Black, White, Latino, American Indian, Jewish, Christian, men, women, famous, anonymous, but ultimately all Americans, all marching for their civil rights.

Source: https://www.nps.gov/articles/march-on-washington.htm

0 Response to "what was the march on washington movement designed to do?"

Post a Comment